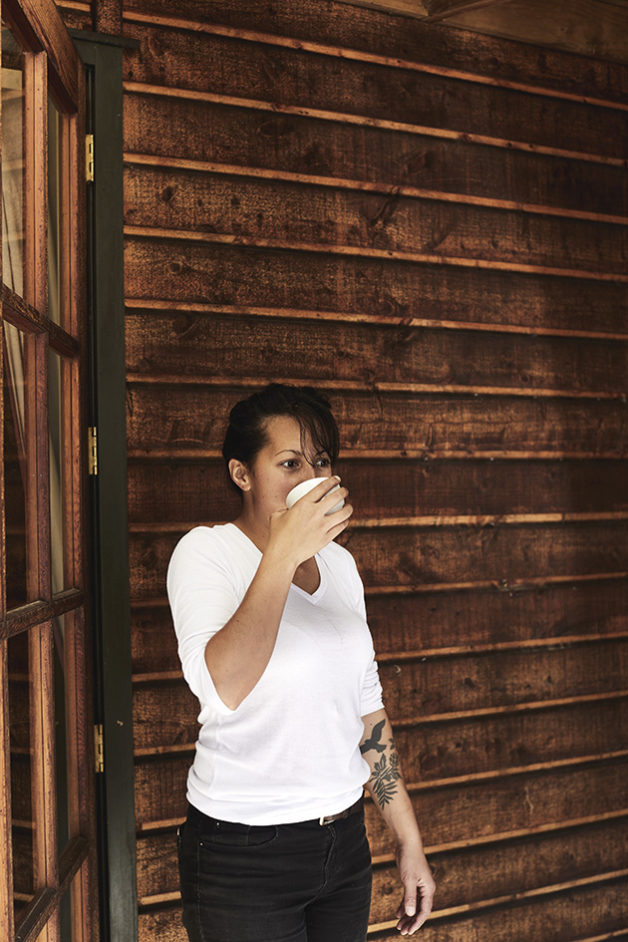

In the beginning of last year, I started seeing the name of this young chef pop up all over the place online and in print media.

Monique Fiso, a chef with a strong vision to explore Māori food and native New Zealand ingredients and turn it into fine dining. I felt really drawn to her passion and vision and her focus reminded me of what had happened with the food scene in Denmark, my home country 10-15 years ago. I wanted to tell her story, so I contacted Monique Fiso to see if she’d be keen to work with me.

Together we created an article for the Norwegian food magazine Nord (read article below), and the beginning of a body of photos that would later turn into many other things. Not just one magazine article but 2, a museeum exhibition (as some of the images will be exhibited this October at MOTAT, Aucklands Museeum of Transport and Technology as part of a bigger exhibition about Innovators and the work Monique Fiso has done with her restaurant concept Hiakai), a tiny feature in a Netflix show (as one image gets displayed in the bio about Monique Fiso, that features in the show) a calendar for year 2020 and a book (a much bigger body of work, which will be published next year), and who knows, maybe more…

During the time we have worked together, Monique Fiso has given me an incredible and invaluable view into native New Zealand food culture, and Māori cuisine. Something I didn’t pay much attention to before I met her. I view her work as something hugely important for the New Zealand food and restaurant scene, but also for NZ food tourism, general NZ culture and identity. She has hugely contributed to putting the New Zealand restaurant scene on the world map (and continues to do so), and I really admire her strong vision and ability to stay true to her purpose. Few people work as hard as her.

Q&A with Monique Fiso, Hiakai

As published in Nord Magazine #24 Sep 2017

By Manja Wachsmuth

(Please note, that this Q&A was written in June 2017, thus many things, including Monique, has developed a lot since then. I’ve chosen to keep this as it was originally written, as a contrast to where Monique is at today with her vision.)

The New Zealand food scene is diverse and influenced by many cultures. Often referred to as Pacific Rim cuisine, almost all corners of the Earths most celebrated cuisines can be found in plentiful here. But something is happening under the radar. Similar to what happened to the Nordic Food scene when Rene Redzepi and Claus Meyer started Noma and founded the New Nordic Food manifesto. Several chefs and restaurateurs are starting to look closer at their own backyard, and what they can find in the native bush of The Land With The Long White Cloud. Up and coming, much celebrated in New Zealand, young chef Monique Fiso, is at the forefront of this foodie movement with her engagement in bringing Māori Cuisine back on the map.

What is your background as a chef and how does it relate to your cultural background?

I’ve been cooking professionally for 13 years, most of which has been in Michelin starred kitchens in New York City. I didn’t grow up knowing much about my culture at all, mainly because I was discouraged from doing so. New Zealand in the late 80’s and 90’s wasn’t as “Māori friendly” as it is today, there was a lot of racism so I grew up being told to act as Pakeha (White European) as possible if I wanted to get anywhere in life. I know a lot of Māori of my generation who grew up in this way also. It causes a lot of self-hate and depression in many of us. It wasn’t until my mid twenties that I started to explore my Māori heritage.

…

Tell us a bit about Hiakai

Hiakai is a pop up series devoted to the exploration and development of Māori cooking techniques and ingredients. I started Hiakai because I really wanted to challenge the status quo on Māori Cuisine. People had this view that Māori cuisine is limited or unsophisticated and that it isn’t possible to integrate Māori cooking techniques or ingredients into a fine dining experience. I’m happy to say that Hiakai has blown that notion out of the water and now a lot of restaurants are integrating more elements of Māori food and culture into their business. Hiakai launched in June 2016 and quickly established itself as a leading innovator in the New Zealand food scene, while also helping play a huge role in keeping traditional Māori food culture alive.

…

What is a Hāngi (explain to someone who wouldn’t have seen it or heard about it before), and how to do a Hāngi at home?

Hāngi is a traditional method of cookery used by Māori to cook food beneath the ground over hot volcanic rocks. It takes almost a whole day to cook a Hāngi, and it’s hot, hot labour intensive work which is why it started to be used less and less with the arrival of the British and the introduction of gas and electricity. The result is food that is incredibly moist and has earthy and smoky tones throughout.

First you dig a pit approximately 3 feet deep, then you place a lot of wood over the pit to create a large fire and place your volcanic rocks among the wood. Light the fire. You want the fire going pretty fiercely for 2 1/2 – 3 hours until the rocks are glowing red. While the fire is going, prepare your food and gather two large containers and fill them each half way with water. In one container place the leaves of two cabbages, in the other container soak 4 – 5 thick cloths that are large enough to cover the hole.

When the rocks are hot, remove them and keep them to the side. Shovel out all the ash and embers from the pit and keep them in a separate pile away from the rocks and hangi pit. Work quickly, your rocks are losing heat as you do this and you want to retain as much heat as possible. Once all the ash and embers are gone, place the rocks back into the hole. Toss your cabbage leaves over the rocks first, then put your food on next, then cover everything with the wet cloths and quickly start shoveling soil into the hāngi pit and keep going until everything is completely covered and the pit is full. Pat down the soil as much as possible to seal the heat in especially around the edges of the pit. If steam appears to escape from certain points, cover it with more soil and pat down. Depending on how large the hangi is or the size of the ingredients inside, the food will take approximately 4 hours to cook.

…

Why cook in an earth oven instead of over open flame?

A Hāngi works more as a method of steaming, whereas fire is direct heat and roasting. Ancient Māori were masters of both methods. Hāngi was an ideal method of cookery in ancient Māori times because they could light the fires, heat the rocks, place the food in the pit, cover it and go out hunting, fishing or take on any other work that needed to be done on the Pā (Māori Settlement/Village), then come back at the end of the day and there would be all this food ready to go beneath the ground. In times of war this method was especially useful because once the pit is sealed, it’s almost undetectable whereas if you were cooking over an open fire your enemy would be able to spot your location from many kilometers away.

…

Tips on matching meat and herbs in the earth oven?

Ancient Māori actually have plants that they specifically line kete baskets with depending on what protein they’re cooking, a sort of guideline if you will. If you are cooking Kaimoana (seafood) or any animal that lives of seafood e.g. Tītī Bird, then the rule of thumb is that you choose herbs, seaweeds and plants that grow along the coast to go in your Kete basket. If you are cooking Quail, Weka or Pigeon you would pick plants and herbs that grow in the forest around the animal’s natural habitat. It’s simple and it works. Of course you can always mix things up to suit your taste. I use a lot of the native plants and herbs to make brines and rubs as well as using them in my linings. Each to their own.

…

What’s the biggest challenge for you, running Hiakai?

The biggest challenge for me is that there are almost no producers or suppliers of indigenous Māori ingredients, and this is a big reason why when people come to New Zealand they can’t find any Māori restaurants. Currently I have no choice but to forage for a majority of what appears on the menu. If I were to open a European, Indian or Mexican restaurant in New Zealand I’d been able to call a few suppliers and have things delivered to my restaurant door, no problem. That’s just not the case with Māori ingredients which is very odd considering we are the indigenous culture of New Zealand, you’d think that foods endemic to our land would be the easiest to get a hold of. Things are changing though, Hiakai is having a tremendous amount of influence in the New Zealand food scene and the demand for Māori ingredients across the country has increased demand so now there are companies that have just begun commercially growing and harvesting Kawakawa, Horopito, Pikopiko, Puha, Native Berries, etc. I’m incredibly proud that Hiakai has impacted the New Zealand food scene in this way in such a short amount of time.

…

What are your future plans?

There’s a lot on the go at the moment. I’m currently in the process of transitioning Hiakai from a pop up into a dining experience that will be a fixed location, it’s going to mean that I can grow my own vegetables and herbs, and also allow me to take the food up another level because I won’t be shifting the entire operation across the country every few months like I have been doing this past year. I’m writing a book on Māori cuisine at the moment, this is going to take some time as a lot of Māori culinary knowledge was passed on orally so to fill the blanks I have to go through historical accounts from early European settlers as well as interview a lot of Kaumatua (Māori elders) from different tribes to piece everything together.

…

How do you think the New Zealand food scene compares to the Nordic food scene? Any parallels?

I feel that the New Zealand food scene is going in the same direction that the Nordic food scene went in the early 2000s. Chefs are starting to look at how best to utilize what is grown locally here rather than using imported ingredients from overseas to create their menus. The subject of “What is New Zealand Cuisine?” has been a topic of hot debate among Chefs, Food Writers and Producers. Our diets and food trends over the past 150 years has been heavily influenced by Britain so most of our restaurants are more “British-New Zealand” than anything else. Slowly New Zealand is starting to pull away from that and people are taking culinary cues from what grows in our own backyards rather than bringing in ingredients from other countries and trying to mimic England, Europe and North America.

…

Explain about the herbs you use (the flavours and other characteristics), and how to swap these for things commonly found in Scandinavia

Just follow the same rules that the ancient Māori did with respect to choosing herbs that grow in the same areas that your chose meat, fruit or vegetable is growing in. At the end of the day, food is subjective. You can pair almost any herb you like with the food you’re planning to put in your Hāngi, just bear in mind you’ll want it to pair well with earthy, smoky flavors and it needs to be available.

Want to read more about kiwi chefs I’ve worked with?

Tom Hishon, Orpans Kitchen

Natasha MacAller, Vanilla Table

Peter Gordon, The Sugar Club